Simply Divine

By Edward M. Gómez

Wildly colored, extravagantly imagined prints of Hindu gods and goddesses aren’t just for worship anymore—they’ve been discovered by Western art collectors.

Shesha Narayana. Lithograph, c. 1910. Ravi Varma Press, Karla-Lonavla

Holy cow, have the New York-based collectors and dealers Mark Baron and Elise Boisanté ever stumbled upon one of the most thematically sophisticated, aesthetically resonant, culturally significant body of images anywhere! And all along, for more than a century, these pictures had been hiding in plain sight, mostly unknown outside their native India, where they have been widely admired but not exactly appreciated as works of fine art.

What Baron, the son of the artist Hannelore Baron (1926–87), a maker of enigmatic collages and box assemblages, and Boisanté, his French-born wife and fellow connoisseur of art and design, discovered during their first trip to India, in 2000, were popular, mass-produced, lithographic-print pictures of an array of well-known Hindu deities. At once venerated objects and ubiquitous decorations, they turned up (and still appear) everywhere in India—on the walls of private homes, restaurants, barber shops; in buses and scooter-taxis; on roadside vendors’ stands; at sidewalk shrines.

They are as omnipresent as, say, crucifixes or portraits of the Pope on the walls of homes and shops in Italy, or images of the Virgin of Guadalupe all over Mexico, but Indian prints of Hindu devas (gods) and devis (goddesses) are far more diverse in their iconography, more multifaceted with regard to the narratives and layers of meaning they represent. Ironically, as big a part of India’s religious and popular cultures as such images have been for generations, only recently have they become the subject of serious connoisseurship and scholarship. Now, with the release of Gods in Print: Masterpieces of India’s Mythological Art (Mandala Publishing), a large-format book featuring reproductions of more than 130 images from Baron and Boisanté’s “Om From India” collection, as well as others from other sources, a rich sampling of this intriguing visual material has been made available to a wide audience in an accessible form. The book includes an introduction and notes about the prints—the earliest of which dates to around 1870—by Richard H. Davis, a professor of religion and Asian studies at Bard College.

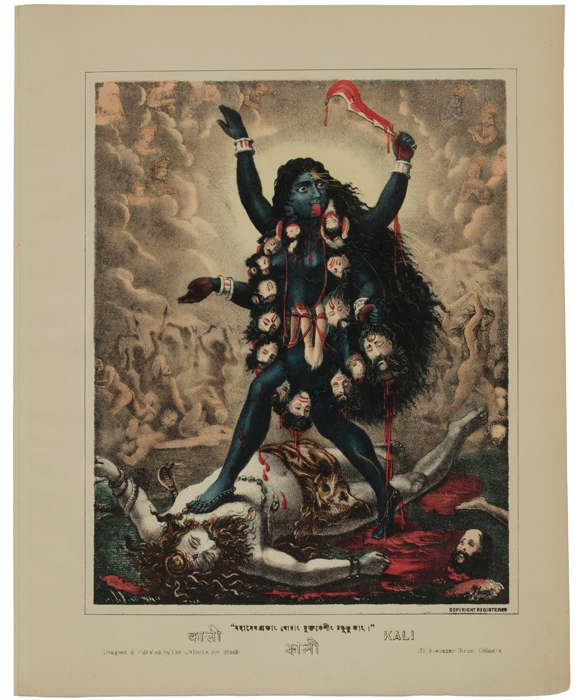

Kali. Hand-colored lithograph, 1883. Calcutta Art Studio, Calcutta

Until 2000, Baron and Boisanté operated a Manhattan gallery that bore their names, where they presented an eclectic range of artists and exhibitions. From the print-making experiments of the American artist Donald Baechler to the cow-dung-impression aquatints and glass “snowballs” of the Swiss-born artist Not Vital, as publishers of original editions Baron and Boisanté have championed artists who have given tangible form to some singular personal visions. “We learned so much as we went along,” says Baron, who in the early days of his career used a press that had belonged to his mother to produce Baechler’s first etchings. Boisanté brought her own expertise to their partnership. She says, “In the 1970s I took Picasso prints from Paris to Japan to sell over there. In 1973–74, I lived in southwestern Japan, and at one point I traveled to South Korea, where, with my then-partner, I bought about 100 antique wooden chests, which we sent back to Europe. I didn’t have a precise business plan, so suddenly I found myself with a shipping container full of antique furniture to sell!”

Baron and Boisanté share an intellectually adventurous interest in what is now commonly known as “visual culture.” That interest found expression in their now-defunct gallery’s mounting of such original exhibitions as “The Sh*t Show” (1996), “Viennese Actionists” (1996 and 1998), and “Trippy World” (1999). Boisanté remembers, with a touch of the dry wit that complements—and tempers—Baron’s effervescent enthusiasms, “The market had tanked when we did the Viennese Actionists shows.” (Those presentations dealt with avant-garde, body-focused event-art of the 1960s.) She adds, “It was impossible to sell art, so we thought, we might as well do this!”

If that kind of quirky pragmatism reflects one aspect of Baron and Boisanté’s approach, so does their wide-open willingness to investigate something completely new when an attention-grabber seizes their collective imagination. “We had closed the gallery and were becoming private dealers,” Baron says. “Then we went to India, not expecting to make a discovery that would change our lives as collectors, dealers and art lovers.” Boisanté adds, “It was supposed to be a vacation; we didn’t head out looking for anything in particular.”

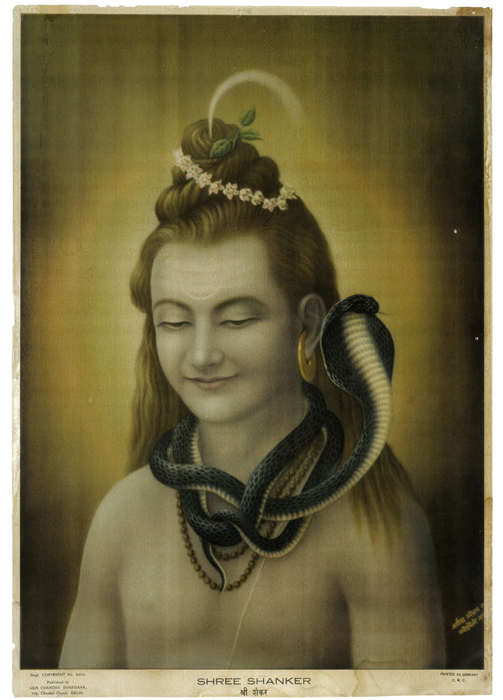

Shree Shankar, offset-lithograph, c. 1935-1940. Hemchander Bhargava, Delhi

What they saw everywhere, though, were pictures of Hindu deities, which, they soon learned, had been mass-produced. Baron says, “Clearly, the newer ones had been made using modern, offset-lithographic printing technology. They were bright and slick but they lacked the warmth and the variations of style and detail we were seeing in what were obviously older prints.” In India’s markets they found stalls filled with the newer prints. They asked boys in the markets to lead them to antiques shops instead, figuring that specialized dealers might have had some examples for sale of the older deity-image genre. Boisanté recalls, “We met antiques dealers, some of whom did have vintage prints, but at that time they didn’t really value them. We were able to start acquiring some of the older, better ones at affordable prices.” The older prints date from the late 19th century.

Baron explains that he and Boisanté threw themselves into researching the subject. “There was and there still is not very much scholarly material available about this very visible, well-known aspect of Indian popular culture. We’ve learned a lot from Richard H. Davis, one of the leading authorities in this specialized field, who has become a friend.” Baron and Boisanté note that once they became hooked on the prints, they began making regular research and scouting trips to India. A meticulous organizer, Baron makes large, foldout, colored-coded calendars with the itinerary of and notes from each of their journeys. He takes great pleasure in handling works of art and has assembled a special carrying case, with acid-free sleeves and cardboard folders, for transporting their precious finds.

In Gods in Print, Davis writes that the “common style” of all of these images is “colorful, vivid, visually saturated” and “direct.” He notes that when he first encountered them in southern India at the start of the 1980s, “people referred to them collectively as ‘calendar prints,’ ‘framing pictures’ and ‘bazaar art.’ In the local Tamil language, they were most often labeled sami-padam, [or] ‘god-pictures.’” Davis observes that many Hindus treat these “inexpensive, two-dimensional pictures with much the same veneration that they might direct toward a divine statue in a temple….Prints of gods could become supports or embodiments of [the deities’] divine presence,” and, as such, as far as the faithful are concerned, “should be honored accordingly.”

Baron says: “With each return trip to India, we ventured further out into provincial regions where we had developed some leads.” Understandably, he and Boisanté are reluctant to reveal the names and locations of the most fruitful sources in a valuable network they have developed over many years but they do note that, for a while, antiques dealers led to some of their prized discoveries. In recent years, so have their visits to dilapidated, colonial-era mansions in remote parts of the country, among whose dusty furnishings “god-pictures” could be found, usually amateurishly framed and in alarming states of physical decline. Baron and Boisanté shudder when they point out that some of the most impressive prints they have found in such houses have been glued to backing boards; in art-conservation terms, that’s a disaster. Baron says, “Often these properties have been inherited by prosperous, younger Indians who don’t want to live away from the big cities; they don’t mind getting rid of this old stuff.” Nowadays, though, savvy antiques dealers, targeting these old properties, have become strategic pickers.

Boisanté adds, “In India, until recently, there has been no market for these prints—not one that regards and values them for their special aesthetic qualities, that is. Instead, for most Indians, they have long had religious meanings and a utilitarian purpose in acts of devotion.”

Both at home and in public ceremonies, those rites, in which Hindu gods are honored, and offerings are made to them, are known as puja. Among the most important and frequently depicted deities in Hinduism’s pantheon are Vishnu, Shiva and Kali. Ganesh, the Remover of Obstacles, with an elephant’s head and a pudgy man’s body, is also popular and turns up in some of the most imaginative “god-picture” art, as does Krishna, an avatar, or incarnation, of Vishnu (who is also known as Narayana). Krishna is frequently portrayed as a blue-complexioned boy with a peacock-feather headdress, playing a flute.

Vishnu is often shown resting upon a giant serpent named Shesha or Ananta (the latter word meaning “endless”), dreaming the world’s creation; that big snake floats in the Ocean of Milk, a cosmic sea. The late American scholar of myths, Joseph Campbell (1904–87), observed that “the world is Vishnu’s dream,” and that “we are all one in Vishnu,” in that deity’s creation-myth vision that “unfolds like a glorious flower.” The dancing god Shiva, usually seen poised atop a prostrate dwarf, has four arms with which to do some divine multi-tasking: With one hand he taps a drum to the unending beat of time; in another, he holds the flame of illumination that destroys the illusion of the world. A third hand points downward, and a fourth hand, palm up, offers a sign of reassurance. Altogether, Shiva’s gestures and props refer to the eternal cycles of birth-life-death and creation-destruction. And then there’s not-to-be-messed-around-with Kali, a blue-skinned, red-tongue-wagging consort of Shiva and goddess of time, change and destruction who wears a necklace of skulls and a skirt of dangling, detached human arms. With her two upper arms (she has four), Kali holds up a bloody cleaver and a decapitated, blood-dripping human head. Kali can sometimes turn up as a manifestation of another Hindu deity, just as her divine cohorts can also assume each other’s appearances in hard-to-keep-up-with, head-spinning tales of transformation, reincarnation, inter-deity relationships and plenipotentiary mischief.

Manhar Krishna, offset-lithograph, c. 1935-1940. Narnarayan & Sons, Jodhpur

Some of the earliest prints in Baron and Boisanté’s collection, from the 1870s and 1880s, were printed in black and then hand-colored. They include some vivid images of Kali, seen traipsing over a prostrate Shiva, whom she uses as a kind of throw rug as she charges forward, wielding her bloody cleaver. These pictures were produced by Calcutta Art Studio, a print-publishing company that was established in 1878. From this same source, the collectors also own a full-color chromolithograph of gentle-looking Sarasvati, the Hindu goddess of learning, which originally served as an advertisement for a company that sold hair oil and assorted tonics. They also have a circa 1880–1900 print from Chitrahsala Press in Pune, near India’s west-central coast, of Gayatri, the wife of the god of creation, Brahma; with her 5 faces and 10 arms, Gayatri sits on a lotus flower. Her central visage looks straight out at a viewer. In his accompanying caption in Gods in Print, Davis notes that this gaze “facilitates the auspicious exchange of glances known in Hinduism as darshana.”

Baron and Boisanté’s collection also includes, among other definitive examples of the deity-print genre, pictures from Ravi Varma Fine Art Lithographic Press, a firm that was set up near Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1894 by the artist after which it was named and his brother. Ravi Varma, who had assimilated European-style oil-painting techniques, made images that were especially expressive and colorful, such as his enthroned Ganesh with his two wives and attendants, or his resplendent, six-faced Subrahmanya, a young god with two female companions astride a peacock, with its fan of feathers unfurled. Varma’s 1894 print of Lakshmi, the goddess of good fortune, standing in a red garment on a lotus-flower platform, was one of the most beloved deity pictures of its time; it helped popularize the wearing of the sari by women throughout India. Baron and Boisanté own prints that were made by other companies, too, including some whose production techniques were influenced by printing experts who had come to India from Europe. As collectors, they have been less interested in the more mass-produced, later 20th-century deity prints whose images were derived from photos, whose colors are more lurid or whose overall character is too kitsch for their taste.

In the U.S., some contemporary artists of Indian descent have been influenced by Hindu-god prints. One is Sanjay Patel, a supervising animator and storyboard artist at Pixar Animation Studios in Emeryville, Calif., and the author of The Little Book of Hindu Deities (Plume, 2006). Like his 2011–12 exhibition at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, his book features his boldly colored, pop-cartoonish renditions of the gods. The San Francisco-based artist Ranu Mukherjee has made a series of ink-on-paper paintings titled “What Color is the Sacred?” whose images refer to aspects of the famous deity prints, such as their backgrounds or their subjects’ poses and decorative details. Mukherjee, who acquired some “Om From India” prints in 2011, says, “My encounter with Mark and Elise opened me up to new avenues of inquiry; I think what they are doing is important for the preservation of the images, but also it adds a lot of depth to the understanding of what these pictures were made for.” The artist notes that, in the U.S., she did not grow up immersed in Indian culture. She says her contact with the prints allowed her to find her way “to working with such material and to really noticing the effect of the limited art-historical representation, which is solely devoted to Euro-American canonical work,” that is typical of “art school education in the West.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has purchased 18 prints from Baron and Boisanté; the collectors donated six more. Other institutions that have acquired some of the prints include the Library of Congress, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, in Massachusetts. Depending on such factors as their rarity and historical significance, the prints Baron and Boisanté have available for sale today range in price from the low hundreds to around $2000.

Boisanté says, “It’s most likely that, someday, we may end up selling many or most of our prints to eager collectors back in India, as the appreciation for this material there grows.” Meanwhile, in the U.S. a diverse group of contemporary artists including Donald Baechler, Philip Taaffe, Jack Pierson, Judy Pfaff and Jane Hammond have acquired some of the prints for themselves.

The spirit of the pleasure Baron and Boisanté take in savoring their Hindu-deity prints and the fact that they stumbled upon them at all may well be best expressed by the words of a modern writer from another part of Asia. It was the Japanese poet Junzaburo Nishiwaki (1894–1982), who, in a little verse from the 1930s, alluded to the ineffable mood of wonder that emerges when “someone whispers with somebody at the door” that “it’s the day of a god’s birth.”

Art & Antiques Magazine, June 2013